It was quite the week, and I am physically exhausted because of it. Deep work on our compensation framework, hiring calls, client event, investor chats, offboarding and gratitude for a leaving employee, HR and onboarding for a new employee, many mails and admin stuff, and all time in between filled with strategic thinking on our identity and go-to-market. All between 7am and 7pm. Sometimes starting earlier or ending later.

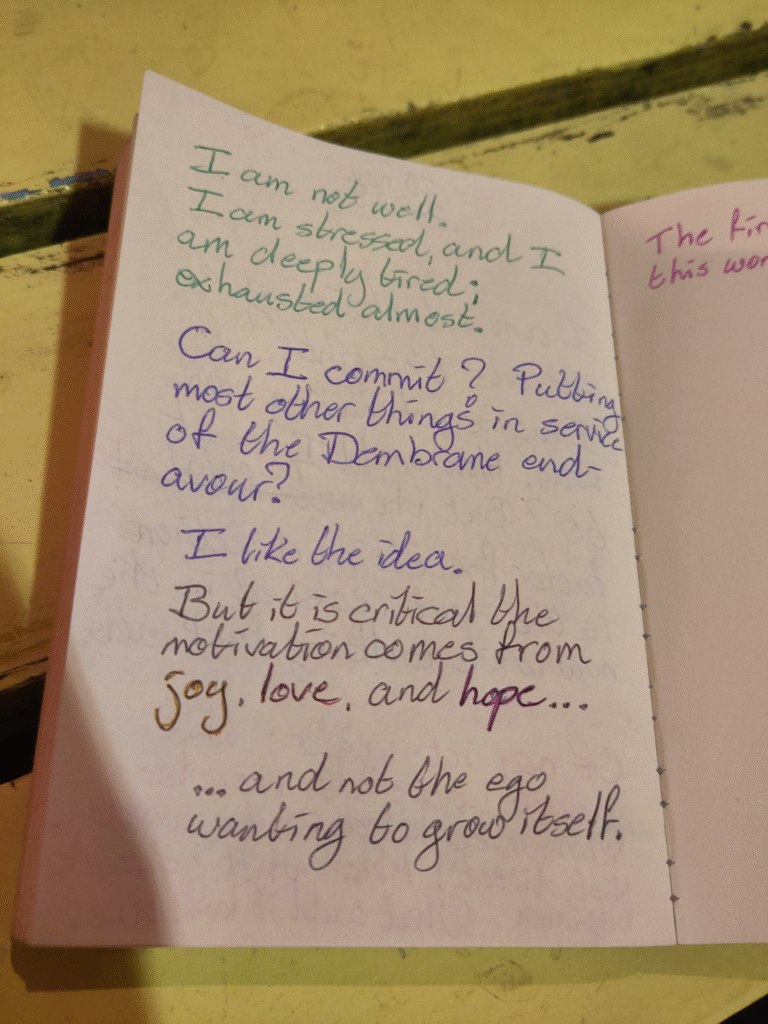

I’ve been noticing serious stress in both my body and mind: my breath cycle is often short, my back is constantly under tension, doing nothing makes me restless, and I have been disliking myself and others maybe a bit more then normally. This morning when I looked in the mirror, I had serious bags under my eyes – I look older then I used to not that long ago. Multiple friends have told me to be careful of myself.

Why? – Why would I work this hard? Many of my friends have had there periods of stress, and all are transitioning towards a more relaxed way of living. Why am I going the opposite direction?

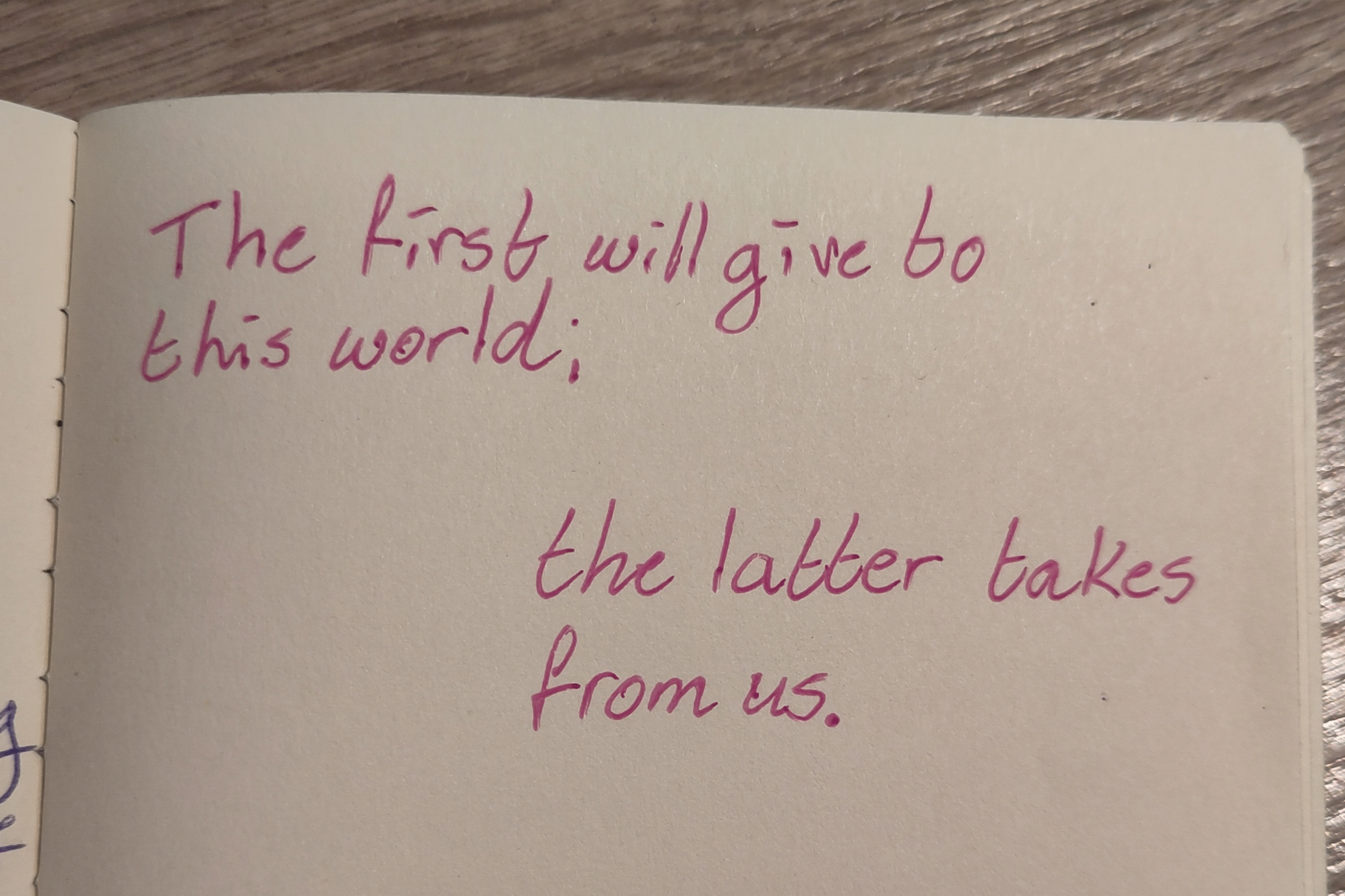

Because I care. I care about our planet and our society. Because I care about the live of the homeless lady who I see getting worse by the day. Because I care about wars, and the millions of lives it destroys. Because I care of the billions of animals that get farmed and slaughtered each year. Because I care about a habitable and thriving planet for our children.

And because I have l hope. I have hope that a better future exists, and that we can build it. I have hope that hard work does make an impact. I have the hope that if the good get more work done then the evil, the good can prevail.

Because imagine if we could achieve the following:

Purpose (the core why):

We exist for the future that becomes possible when we truly hear each other.

Vision (the what):

We envision a world where democracy works for everyone.

Mission (the how):

We make it easier to make sense of big, messy conversations, so everyone can shape what happens next.

The one-liner: Together we make sense.

The core belief: PEOPLE KNOW HOW

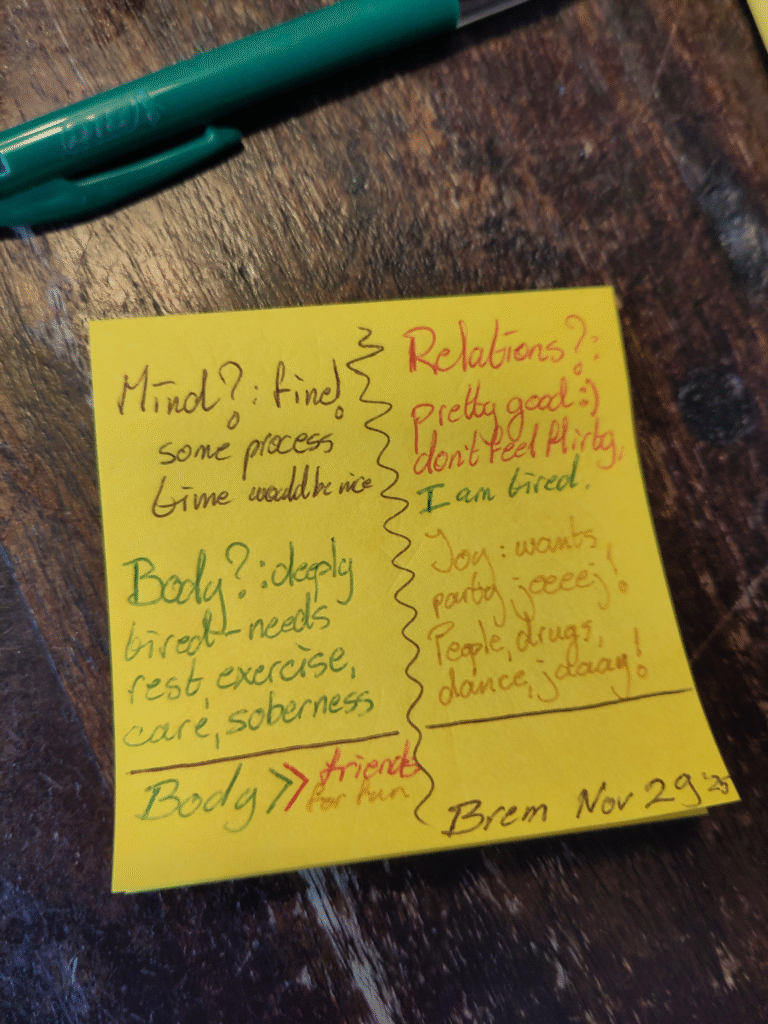

Bonus: Example of using my framework of life in daily priority decision making

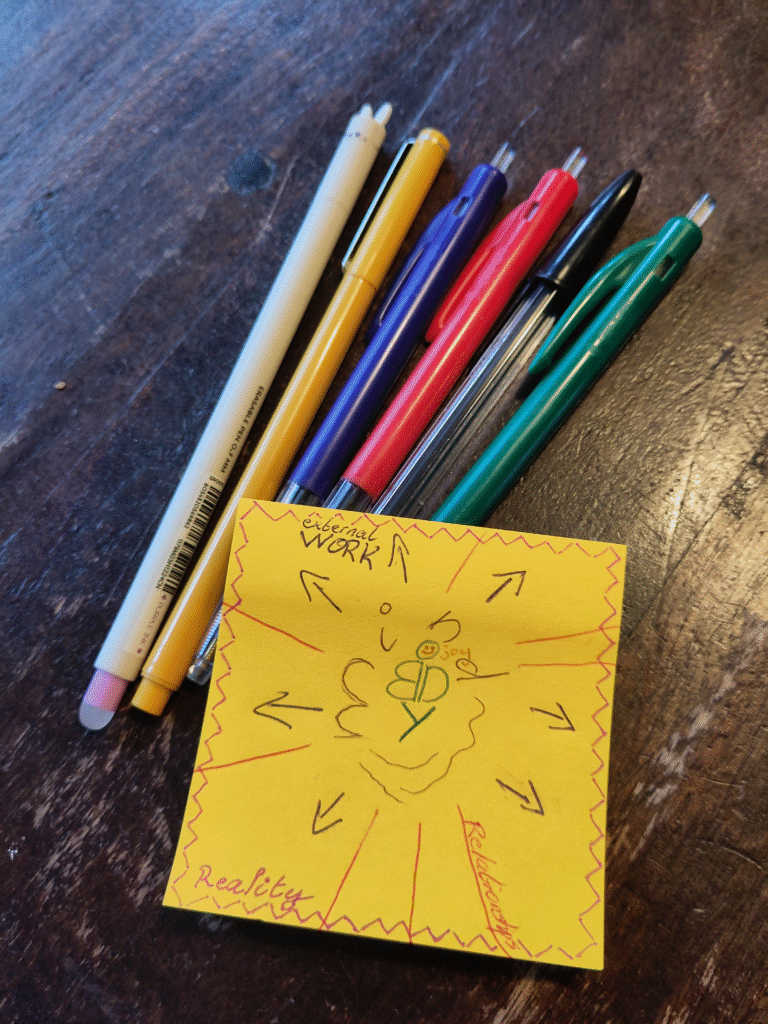

A drawing of the framework with body, mind, relationships, joy (together I), external work, and reality.

Since I know I prioritise body > mind > relationships > joy > work; I knew that if the body had conflicting needs with friends and joy, I should choose what’s best for the body.

It was not fun. I was sad to let a friend down and to not have a great evening. But I’m an adult now – decision making is often not fun. Life can be sad. And running away from sadness will lead to much more suffering in the long run.